Dopamine Revisited

Dopamine is both a reward and a measure of the reward. It's why you know you want something, and how you know you've found what you want.

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:00

Honestly, I didn't quite see the entire end of it. But things are happening.

Eric 0:06

You need to see the end.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:09

I went back and I saw some things, but. Yeah.

Eric 0:11

Hey. So today is Friday, January 19th. We've taken a long hiatus due to holidays and, you know, illnesses like COVID, which are happening these days.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:22

We had holidays, we had COVID.

Eric 0:23

We are back with what is this episode? This is this is episode two of season two. Hey, Josh.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:29

Hey, Eric. How's it going? All right. Okay, so I've been preparing for a class that I am going to be teaching Introduction to neurophysiology. And I've been focusing on dopamine. And it's based on my original research on dopamine that I've already talked about a little bit. But as I've read all of the other people who have been working in the field, I thought I needed to address some of what they've been talking.

Eric 0:54

I'm sorry. I just want to step back. What is the name of the course.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:58

Introduction to neurophysiology?

Eric 1:01

Is this of course you've taught before now. Oh, fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:03

This is not a course I've taught before and I am not teaching the way the course is normally taught. I'm not using a textbook. I'm making it all up. One of the.

Eric 1:11

Yeah, that's, that's, that's one of the things I like about this that you wouldn't use. You do a new course. You have to, you have to decide what you're going to do and learn it.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:20

Exactly. Yeah. So normally when someone would do a new course they would pick the textbook and then the syllabus would follow the textbook. But instead I have a bunch of ideas and then I have to find papers that follow those ideas and I have to do this for undergraduates, which is a little bit complicated because some of the papers are for, say, postdoctoral students. Yeah, and other them. Others are more for an introduction to high school students. And in between there is some things my students can actually read and learn from, and it's difficult to find exactly what they are.

Eric 1:50

This is great. It's making you do a lot of work.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:52

It's making you do a lot of work. And then the other problem is I disagree with the fundamental, fundamental model of dopamine as it is presented. And so the readings I have are all about what that fundamental model is, but the actual lectures are going to be something else entirely. So this is going to be unusual for the students reading something that then the professor is arguing against. So if they study and learn what they're reading for.

Eric 2:18

Undergraduates.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:19

Yes, it's a little difficult. So what I'm doing.

Eric 2:23

As an undergraduate, I have a lot of respect for undergraduates and the work that they do, but this is very different. Do you think they can handle it?

Dr. Josh Stout 2:30

I hope so. I hope so. Mostly it's going to be listening to me and I explain it to them. And then the background reading, which they wouldn't do anyway, is going to be okay. Sorry. Honestly. All right. So they were going to be listening to me anyway and reading my notes. That's all they ever do. And this is.

Eric 2:48

Interesting. So maybe after they come in once or twice and they hear you arguing against something that they have not read, they might get interested enough to.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:56

Actually, they might. But I will also be explaining that as well. So they just want everything given to them honestly. And I will be doing that. And I'm happy to do that. And if they need to do any extra studying, I will have provided papers for them in the field.

Eric 3:12

An will you give them opportunities to show that they've done that work?

Dr. Josh Stout 3:16

I, I will be testing them and they will have to know some things and then they will be making a poster and presenting it. So anyway, what my research had shown is that dopamine is not a stimulant, it's inhibitory. And that's what started everything. And I tried it a bunch of different ways and it was quite conclusive. However, there's no one in the field arguing it is or isn't a stimulus. They're just accepted. That is a stimulus. And let's move on. And now we'll talk about what dopamine does. So they've left behind the whole part that I'm actually disagreeing with. And so there's a new understanding of how dopamine works. Dopamine had been understood as a reward substance. It is now no longer understood is the thing that makes you feel good. It is understood as the thing that makes you want to feel good, not the thing that makes you feel.

Eric 4:07

And this is as of when When did this change?

Dr. Josh Stout 4:09

It probably started in the nineties, but it has become more and more accepted through the 2000s. And so this is mostly coming out of a group of people called affective psychology. So affect so in a was an A Exactly. So these are people who are behavioral psychologists who are studying facial expressions in response to things and in this case what they're just looking at is do you stick your tongue out and dislike something or do you suck heartily on the thing and enjoy it? And so it could be cocaine or it could be sugar. Those are pretty much the two things they use. Mostly sugar. And what they've shown is that rats or people like sugar, even if they have had all their dopamine blocked. So a rat who has had their brain surgically altered too, so that they're not producing dopamine will happily suck on sugar water and or cocaine. And someone with Parkinson's disease who is not producing dopamine will still enjoy the taste of sugar will say, Yes, I like that if is sweet.

Eric 5:13

So so the idea here is that the with with dopamine with no dopamine at all, you can still.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:20

Enjoy.

Eric 5:20

Enjoy things.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:21

Yes. Yes, exactly. And people who have low dopamine and are depressed and can barely go to bed still feel pleasure. So there's a difference between the idea of pleasure and wanting something. And so the model now is, is that dopamine is the stimulant that causes you to move towards a reward. And it's the thing that makes you want the reward, and it's the measurement of the reward. So this is the current understanding.

Eric 5:47

It's both the the the pre meaning, the thing that stimulates you to move towards the reward. But yet it is also the measure of the reward received.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:02

But not the reward. Yes. And so I find this confusing.

Eric 6:05

But how can it how can it be something before you receive the reward and then also after you get. It's both. It's both.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:12

And it kind of has to be both. Okay. What I have problems with the idea of something being a measure of a reward, but not the reward itself. And so the studies show that if you block dopamine, an R in a rat, it falls flat on its face. It's not going to move anywhere. It has no desire to go anywhere ever again because it wants nothing. But if you actually saw it.

Eric 6:36

So the idea being that it would literally lie there until it died.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:39

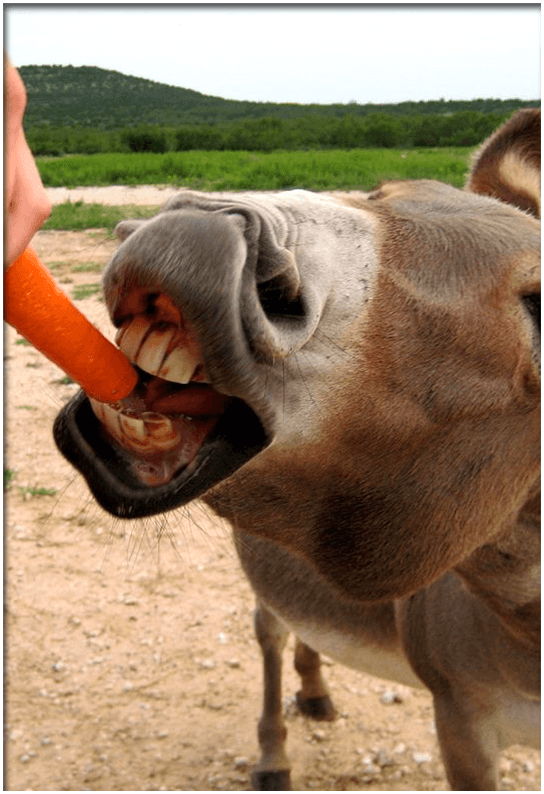

Yes, but if you put sugar water in its mouth because it doesn't want anything, it has no build up of wanting because it has no access to dopamine. But with sugar water in itself, it sucks happily on the sugar water so it doesn't know it wants the sugar water, but it enjoys getting the sugar water. So this is a separation between liking and wanting. And I think this is an overly complex model and I think it misses the fundamental nature of what dopamine is, which is an inhibitory reward substance, not a stimulatory substance that makes you want something, something that it would be inhibitory, wouldn't encourage wanting in the same way, whereas something that's eye stimulatory also would then be a problem when you've finally got the reward because it would make you move away from the reward because it's stimulatory rather than staying there. And so my, my model of dopamine is essentially based on the carrot hanging in front of the donkey. And I've said this before, but now I understand exactly what's going on a little bit more. So the ancient Greeks, when they thought that vision worked by having little objects go into your brain or into your eyes and they would actually be sitting in your eye. And so now we understand that obviously there's nothing going into our eyes from the outside.

Eric 7:58

I actually believe that there was a physical thing going into. Right.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:00

So in some.

Eric 8:00

Way we know that there is, but not the way they thought.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:03

Not the way they thought, or that maybe something was leaving your eyes and then sending it out and that information was coming back to it. They had all sorts of ideas, but they didn't understand how anything worked. And this obviously not how vision works. However, if you think of an organism living in the water trying to find something, it's going to be using smell and smell and taste. If you're sitting in the water, essentially the same things. And so smell and taste are little bits of the thing you want. So it's a little bit like the original Greek understanding of vision to start to see something, perceive it with your taste, smell in the water, you're actually going to get a little piece of that thing you're tasting smelling in order to know you're looking for the right thing. Okay, so my whole model is based on that. And so let's say there's some food in the water and there's little bits of amino acids. The number one amino acid that we all respond to is glutamate. So monosodium glutamate is the thing that makes you taste things as savory as as as as meat. There's only five flavors. Two of them are rewards, sweet and savory. Two of them make babies and rats stick their tongue out and frown so sour and bitter. And then salt sort of depends on how much salt you have. Both the glutamate and the glucose can go through the brain blood barrier and can directly stimulate reward pathways. We don't know exactly how all of this works. More and more I'm finding out if it if I don't know something at this point, it's because it probably hasn't been known. I'm not boasting that I know everything in the field. I just keep running into these walls that just find out that we really don't know these things because it hasn't been tested.

Eric 9:45

So the models have a black box.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:47

That they're fake. So, so, so something you like goes in sugar or glutamate and your brain says, Suck that down, eat it up essentially.

Eric 9:59

Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:59

More the more Exactly. And so the models of how what they call repetitive behavior appetite stimulating behavior works is that you have a lack of something. You feel uncomfortable, hungry or, you know, sexually aroused. You really, really want to go find a reward. A lot. By the way, a lot of this modeling was done by men. So sex is a lot of sort of the metaphors that people are using. Sex definitely has a desire and then a very, very obvious reward moment. And then your your your you're no longer desiring for a while and then you slowly become more uncomfortable as you're seeking it again. However, I think food is a better model for this one because there are things that don't have sex that and you still need to eat. Food comes prior to sex in evolution. And unlike, you know, sexual release when you're eating, you still need to have some of that desire. The desire and the eating are happening at the same time. Mm hmm. So it's it's a it's a more complicated system. And I think it's it's more fundamental.

Eric 11:15

And more inherently complicated.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:18

System. Yeah. Yeah. So the idea is you haven't eaten, you want food, you then seek out food. You see, you get food signals, you get excited because you get those food signals. You seek out that food, you get the food, you're getting rewarded. So you hold still and eat that food. And at this point you're sated and you don't look for food anymore for a little while. And then the whole system repeats itself. Okay? So in my system that glutamate would go through the water, glutamate directly stimulates a little bit of dopamine. And so the dopamine this this is known.

Eric 11:54

It enters through into the bloodstream, right into the brain.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:57

And yes, and this would be not just for a crayfish and shrimp, which I was studying, but also for a human. You actually get glutamate going into your brain when when you eat it.

Eric 12:06

Right from my mouth to the brain.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:08

Right to the brain. Right to the brain. Exactly. So these these are conserved pathways. So in evolution, we talk about saying that you see everywhere there's a well conserved pathway, that glutamate stimulates dopamine. What does that dopamine do? It says, let's keep looking for more of what we're getting. We want to find more of this food so a crayfish in the water will move towards a gradient that gives it more glutamate in one direction.

Eric 12:35

Sends a little glutamate over here, I sense less. No, no. Go toward food. Good things more. Yes, yes, yes. Tuning in a radio.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:41

So. So. Every time they're going in the right direction, they get a little bit more reward. The dopamine. Yeah. So this is my model now. Yeah. Okay. So imagine you have a donkey running after that carrot on a stick. Mm hmm. Okay, so the donkey can see the carrot, but in this case, there's no vision. So this is basically a donkey looking for a carrot on a stick, getting little bits of carrot and tiny little bits of.

Eric 13:05

Carrot a little.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:05

Bit. And as long as it keeps getting tiny little bits of carrot, its nose is going in the right direction. It gets no carrot, it stops, it goes in the opposite direction. So my understanding of what researchers have been doing to the rats when they give when they block dopamine is they've been blocking those little bits of carrot. And so that that little, you know, donkey mouse crayfish doesn't get those little bits of carrot. And so no longer goes for the carrot. No hope. There's no hope. There's no point to it.

What dopamine does, in my opinion, and somewhat the research supports this, is it signals that there is hope, there is something to go for. Yeah, yeah. And then the dopamine goes directly to both reward centers and places in your brain where it is converted into epinephrine, adrenaline, or epinephrine, all basically the same thing. So the dopamine directly becomes a stimulant.

Eric 14:08

Which is in itself a reward, is it not? It's related to a reward energy.

Dr. Josh Stout 14:15

I suspect these are related to the dopamine rewards and that the energy is there to keep you moving so that you get a little bit of dopamine you and say, I'm done. I say, I want a bigger reward. I'm being I'm being given dopamine. So I'm in a constant real time measurement of I'm going in the right direction, I'm aiming for the right thing, and I'm getting stimulated a little bit by that epinephrine so that I keep moving.

Eric 14:43

So then what happens once you get that meal and you get the big payoff?

Dr. Josh Stout 14:47

Okay, once you get the meal, now you're getting a major reward. So you're getting more dopamine. Yeah.

Eric 14:52

Like all at once.

Dr. Josh Stout 14:53

All at once. And I think there are other things that are happening as well. So part of the reason that people think that dopamine is no longer a reward, but it is just a thing about wanting is there ordering is measuring wanting. Exactly. It's just confusing to me. Yeah, exactly How much money do I have? It's the money in my head. This is like something like, not the money. It's some sort of measurement of money, but not money. Anyway, it makes sense for me. It's the money is the measure of the money. Yeah. Anyway, so there are opiates and there are cannabinoids. These are the two molecules that directly signal liking as the afferent, as the psychologists call it an afferent. But the affective psychologists. So they they there's wanting and there's liking. And so dopamine makes wanting in their opinion, and the opiates and the cannabinoids make liking. Mm hmm. Okay. So I think both sugar and glutamate and various drugs are signaling the liking things in these two very small pleasure areas. Dopamine tends to - it signals in a much larger area called the nucleus accumbens. It's underneath the brain, essentially. These other two smaller ones are in it and they talk to each other. So the two smaller pleasure centers make dopamine and the and the dopamine signals these pleasure centers. So what you do, if you block dopamine, you can still feel the opiates and the cannabinoids. So I'm not denying that I agree with that. So you can actually block dopamine and still have liking dopamine because it's also a reward, in my opinion, is the measure of the reward, because it's how much dopamine you make when you're stimulating the opiates and the cannabinoids. They're also releasing dopamine. So they're also saying, yes, you got that reward. So that reward is the measure.

Eric 16:53

Of the reward. So the opiates and the cannabinoids actually not only turn into epinephrine, but they also talk to you. The dopamine treat.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:03

Dopamine turns into epinephrine and they signal more dopamine to be created.

Eric 17:10

So, so right, so, so right. So dopamine is coming and going.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:16

It's dopamine is coming and going. And all of these things talk to each other. It's why I don't deal with people much, because all of these centers are signaling each other as well. And a lot of them are black boxes. This is all done with functional magnetic resonance imagery. And so it's correlation, not causation. We just know there is there are correlations with certain things that we call liking that happen in these pleasure centers that happen if you directly inject opioids into these pleasure centers, you get the like. But it's like.

Eric 17:44

But it’s fascinating because you have the you have the to that you meant the cannabinoids in the.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:49

Opiate.

Eric 17:49

Opiates are specific. But the way you describe it, the the the dopamine is a more generalized thing that affects more. So if you were to shut that down, the sense of like being certain that there can be no satisfaction, yes, I can. And then and then once, once something stimulates the cannabinoids in the right opiates, then ha. But then once it stops, there's just still nothing yet.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:16

Exactly. Exactly.

Eric 18:17

And you're certain, right?

Dr. Josh Stout 18:19

And you're certain. Exactly. Because all the little carrots have been blocked, Right? All those little carrots that that shrimp gets have been blocked.

Eric 18:25

Well, having done none of the reading, the way you describe it, it sounds sounds perfectly reasonable.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:29

Exactly. Yes. So small amounts of dopamine are known as what's called tonic dopamine as in muscle tone. So if you remove tonic dopamine, you have no muscle tone, you just collapse. You just have nothing. And so this constant supply of small rewards in the form of tonic dopamine are also stimulating epinephrine, keeping you moving towards that reward. And then the opioids and the and the cannabinoids are the sort of really obvious liking signal. But dopamine itself is a liking signal. The liking signal gets stronger in the presence of dopamine, but without dopamine, you can still like it. So again, dopamine is liking and is wanting because you want a reward. Now think about what these things are. I'm including dopamine with opiates and cannabinoids. All three of these things, in my opinion, are not stimulants. They are inhibitory, they're not inhibitory, and then they stop something. But when you get them, you stop moving, right? You stop seeking the thing you're looking for because you've been rewarded.

Eric 19:34

Except the dopamine, which you said very.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:36

Small amounts of dopamine keep you moving, but a large reward. You sit and eat the food pellets, right? So the crayfish stops looking around, even though there's a lot of doping in the water near it. Right. You can smell dopamine, but it's getting the dopamine. It's also getting the opiates. It's also getting the cannabinoid because it's found the right thing. These things respond to a whole bunch of different chemicals, particularly the cannabinoids, respond to a bunch of fatty acids. And so the crayfish has found its food and stopped moving. But when it's looking for food, it's not getting little bits of cannabinoids and it's not getting little bits of opiates to tell it where to go. It's getting little bits of dopamine. So dopamine is the direct measure of small amounts of things that you want to cause you to seek that thing. So bright lights, flashing colors, good smells nice sights, things you're attracted to, that's all measured by dopamine, but it's also rewarded by dopamine in conjunction with these other reward molecules. In the current model, dopamine would be a stimulant. They would be inhibitory because they're because dopamine is not a reward, in my opinion. Dopamine is a reward and is just like these other ones. They in large amounts. When you get the reward, you stop moving. It would be really interesting to see if you can cause liking in the absence of opioids and cannabinoids. This is not been done with.

Eric 21:02

With only dopamine?

Dr. Josh Stout 21:03

With only dopamine, right? So because you can block dopamine, you can still see that there's liking in the presence of these other things. It hasn't been done in the other direction. What I have found in my research that has not been done elsewhere that I'm realizing is important now that I've been going over this stuff is I have shown wanting when dopamine is blocked. Now I've shown this in a short term so I can give something glutamate and it acts just like there's the smell of food in the water. So it's exactly the same without dopamine, just just glutamate. It acts like it acts like there's food in the water. So naturally, it would be now producing its own glutamate inside. Yes, I can give it Haloperidol, which blocks dopamine, and it still runs around just as much as if it had been smelling the food.

Eric 21:49

Really.

Dr. Josh Stout 21:50

I don't know if this would continue in a longer term project. So one thing that I've seen in a couple of a couple of bits of research that tends to be downplayed is after you give something Haloperidol, there seems to be an initial excitatory phase. So when something gets haloperidol, at first it's getting no carrot, so it really wants carrots. And so at first it'll push that button a little bit faster and then it will give up. And so I might have been only doing my experiments on crayfish in that initial bit. And so initially Haloperidol has no particular effect because there wasn't that much dopamine anyway, right? There was only little tiny carrots. And that in that, in that crayfish donkey brain. And so by blocking it, it still wants stuff. It's still, it's still seeking how it knows what to want. I don't know. I'm wondering if there aren't more than one reward. We know there's these two other molecules. It might be getting small amounts of cannabinoids. It might be getting small amounts of of of opioids. So there might be more than one reward and desire pathway. We know that people who are blocked from getting say, you know, heroin really, really want more heroin. Mm hmm. And that is a measurement of reward based on opiates. Now, opiates are, again, related to dopamine. So the current model is all of that wanting for heroin is coming from wanting triggered by dopamine that is then satisfied by the presence of opium. Okay. So, so, so so the idea is that the wanting has nothing to do with the opioids.

I disagree. I think all the rewards that reward that.

Eric 23:41

Well, that kind of intense wanting is only created by the presence of the opioids.

Dr. Josh Stout 23:46

The lack by by what you used to have, and now you lack.

Eric 23:49

It. But but it's only created by the initial elevated level, which is then a renormalization. Right. And then the lack.

Dr. Josh Stout 23:59

Right, right, right. So, so the the model of wanting being a separate function from liking I disagree with I think the more you get what you like, yeah. The more you want it. And so.

Eric 24:14

It just seems like.

Dr. Josh Stout 24:16

Exactly my.

Eric 24:17

Model isn't like that.

Dr. Josh Stout 24:18

Exactly. My model is simpler.

Eric 24:20

Why would that not be so right?

Dr. Josh Stout 24:22

So so. So some of the arguments against this is if someone is a cocaine addict and you block dopamine, it reduces their cravings for cocaine, but they're still happy to ingest the cocaine when they get it. So just like the rat given Haloperidol. Yeah. However, it never lasts. It never works because there is this more or less constant lack of cocaine, which even if you are not feeling the wanting associated with dopamine for some, somehow you still want it. So I think the dopamine is a larger signal for desire, but that the opioids and the cannabinoids are also rewards and also signals of desire.

Eric 25:11

How could anything be only one thing when everything in life tells us that everywhere we look, nothing is any one thing?

Dr. Josh Stout 25:19

Well, it's true. And it's it's it's no matter what model you use, you have to be able to go back and forth between wanting and the gratification of the thing you want.

Eric 25:29

And also, it's fascinating. I mean, the first time you told me the dopamine actually directly just turns into epinephrine, It's like. But so so one thing is literally not one thing. Right? Right. Literally becomes something else becomes something on the body.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:45

Long Right. So the dopamine is the reward and epinephrine is the stimulant to move towards the reward. And so if you have a little bit of dopamine, it's turning into a little bit of epinephrine and you move towards it. Now, no matter what model you use, once you start defining things strongly in a model, there's going to be problems with your model. But I think I'm answering more of the problems with the existing model, with my model than the one where you're separating. Dopamine is not a liking drug. It's a wanting drug purely on. One of the things that makes more sense in my model than in the existing one is ADHD. So the current model of ADHD is you're hyperactive because you have a low amount of dopamine. So if dopamine is is a stimulant, then more dopamine would not be recommended. Whereas if dopamine is inhibitory and you give someone who has ADHD, dopamine, they're going to be able to concentrate better. And this is what we actually do, right? So when people have ADHD, we give them stimulants that stimulate dopamine.

Eric 26:53

Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:53

And that dopamine.

Eric 26:55

Oh, I never does this. This stimulants. What they do is they stimulate dopamine.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:59

Yes, exactly. You realize the amphetamines. Exactly. And yes, you get stimulated because that some of that dopamine is turning into epinephrine and it stimulates.

Eric 27:07

Activity.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:08

And it will be activity. And this holds true for ADHD people, ADHD people as well as anyone else. There's some people out there who think that somehow stimulants don't affect ADHD people, that for whatever weird reason in their brain that stimulants are inhibitory to ADHD. But it's not true. Stimulants are stimulating because of epinephrine. Your heart will go faster, your appetite will be reduced. All of these things, however, the dopamine is making you feel like you've found the thing you're looking for. And so you stop some of that seeking behavior that is associated with low dopamine. So in that a repetitive cycle that we are talking about, people who have ADHD are always in that part where they're a little uncomfortable and they're starting to look for that next set of rewards.

Eric 27:55

Whatever that is.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:56

Whatever that is, no idea what is right. And this is the weird thing about our brains is we don't know one dopamine from another. So, you know, we can we can we can transfer one kind of reward for another. So when we're depressed, we eat lots of food because it makes us feel better, because we get those rewards and we're less depressed. All of these things. Yeah, Yeah. So, so this is what people with ADHD are always looking for. And also, I think why they can hyperfocus. So one of the sort of superpowers of ADHD is yes, you have lack of focus, you're always looking for other things. When you really get into things, you see nothing else in the world.

Eric 28:35

The whole world disappears.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:36

And I think what's happened is you've triggered that dopamine reward. When you found something you really like, you get into it. Even deeper than other people have because you've been so, so seeking that. Now you've found your reward. And again, it can be anything. It's not it. You could become a drug addict or you could become a painter, or it could be anything that gives you that satisfaction. There is no difference to the dopamine. It's all it's all the dopamine. But fundamentally, I think dopamine is an inhibitory reward. It is not stimulatory and that it is something where you need small amounts to move towards a goal, but it is still the reward given to you with the goal. It works with other rewarding molecules, the cannabinoids and the opiates. But it itself is also a rewarding molecule and acts just like them. When you get a big reward, you sit still and just smile, right? That's what dopamine does and it's coming out of nowhere to do. And that's what the opiates do. And when you don't have those things, you start seeking them. This is what all of these things do. And so I think rewards are the measure of the of of the wanting.

Eric 29:52

Okay. The rewards are the measure of the wanting. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:56

So the bigger the reward, the more you will want it. If you see a bigger carried out there, you're going to want it more fascinating. All right. So that was basically my talk for a short while.

Eric 30:05

So what you've so you what you've done though before I before I let you finish, you've turned it around. It's it's the measure of the wanting, not the measure of the reward.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:14

Right. So that what want want wanting.

Eric 30:18

The.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:19

Yeah. I mean so, so previous to this it would be something that gave you a lot of dopamine, could make you want something but then you might not enjoy it when you got it in this, in this model, when you really enjoy something, it makes you.

Eric 30:36

Want that you wanted that much more.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:38

That much more. Exactly. And to me, that makes much more sense.

Eric 30:41

Everything you've been saying just seems to make sense. All right. Well, yeah. Thanks, Josh. That was fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:47

Yeah. Just a quick rundown on where I'm going and what my next semester is going to be, and then I'm going to start doing some experiments and I'll I'll have some more answers. But this is going to take you.

Eric 30:54

So, so so I mean, this that that was my next question is how do you how do you find results that prove what it is that you're saying?

Dr. Josh Stout 31:04

Well, nothing is ever proven. But I can I can I can show things in that that'll support my my ideas. And the main one is, is that dopamine is not stimulatory. I love and I can show it again and again and again.

Eric 31:15

So so then am I sitting here hearing the genesis of of the work of many students to come? Yes. Oh, I love it.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:24

Absolutely. Yes. This is going to be years of work.

Eric 31:26

Fantastic. All right. Have fun, everyone. All right. Thanks Josh.

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa