Out of Africa or From Africa

How climate change, genetic bottlenecks, and migration work together to make the Nile the tree of life for our African species.

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:00

We got weeded down, down to a few tens of thousands of people periodically. And so we became very homogenous because of this. Whenever we would mix together, there was only a limited population that became almost completely homogenous. And this is one of the points I wanted to make of how not different we are from each other. Yes, we groups of us evolved separately in different places over hundreds of thousands of years, but there was always this mixing together and homogenization as populations crashed and it was one of these tiny sort of splinter populations that was able to go across, you know, the Sinai and get to the Middle East and then was able to spread out, interbreed with Neanderthals and then spread out across Europe.

Eric 0:46

And kill everything else.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:46

And kill everything else, including Neanderthals. But that's our history that we we always competed with, you know, the other people we would meet and then also interbreed with them.

Eric 1:03

Today is Friday, August 30th. It is the end of what has felt like a very long, hot summer, the hottest summer in recorded history. How are you doing, Josh?

Dr. Josh Stout 1:13

I'm doing well. I'm glad to be back here. Thought we'd get a lot of work done during the summer, but it turned out not to be that way.

Eric 1:19

It was a it was a busy summer.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:20

It was a very busy summer between kids and sweltering. We didn't we didn't get any recording done. But I'm glad to be back. And I'm particularly glad to be back because I want to address something that a mutual friend of mine, Robert, has brought up and I just want to really address this head on because, you know, he's a friend of the show. He does the music for our show and he's a smart individual who I want to engage. So he's probably listened to this more than anyone else. And he went back over the summer and listened to all the shows, and he pointed out that I say when humans left Africa and that this could be problematic, which had not I had not thought about this, it had not occurred to me.

Eric 2:07

There are still people there.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:09

Exactly. There are still people there. And I obviously wasn't thinking of it that way, but it's definitely something that needs to be addressed, particularly because people like me, i.e. white males, tend to think that they're speaking about everyone and themselves at the same time when they say we and it's a sort of unconscious bias that happens all the time. You know, one giant leap for mankind, you know, one giant leap for man and one giant leap for mankind. Thank you. All right. Completely forgot that.

Eric 2:41

One step for man. One giant leap for mankind.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:43

And completely got that wrong because they're the same thing and couldn't figure out how to say it. But that's the typical kind of stuff that men tend to say, particularly white men. And so I just wanted to address this, that when I'm talking about people leaving Africa, there were obviously people still in Africa and that the bias on my part is largely because I couldn't even imagine it any other way that when I talk about people coming from Africa, obviously Africa is primary. It's not just the soil from which we grew or even the roots. It's the soil, it's the roots, it's the trunk, and it's most of the branches and only one tiny branch. It was able to leave Africa and then spread across the world. But the the humanity is from Africa and has always been in Africa. And it is it is only a very minor, minor portion of our of our population that was ever able to leave.

Eric 3:48

And then what happened was they didn’t, we didn't leave - humanity spread.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:52

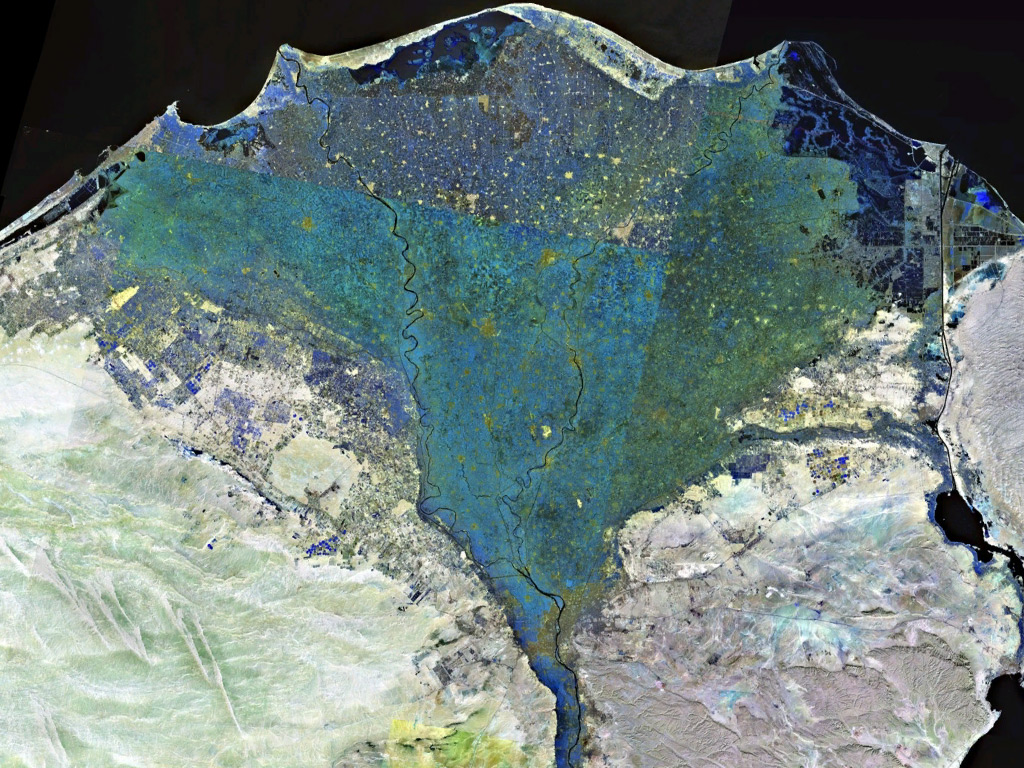

Humanity spread. Yeah. And it's and it's always been that and it's it's very difficult because of the history of racism and the way we think about race to see this connection. We we think of sub-Saharan Africa as some sort of separate thing. And it is by no means that way. And so it comes out in the way we talk about things. So we have this phrase out of Africa. It's been there since since the Romans Siempre, Nova X, Africa. There's always something new out of Africa and that we think about there is this this place and that we come out of it and we really need to think about it as we come from it. Mm hmm. And I just wanted to emphasize that. And I wanted to talk about one of the sort of misconceptions that I think is still happening because of this problem of really seeing sub-Saharan Africa not being connected. Now, the problem is the Sahara. In some ways, the Sahara is this huge desert blocking Mediterranean culture from the these the southern African cultures. And so from the Egyptians to the Greeks to the Romans, we thought of Mediterranean culture as essentially being this separate group that then gave rise to European cultures. To a certain extent, Asian culture. Certainly we we left from this area. And I just wanted to emphasize how not true that is and that this is based on two things. One is it's based on the sort of happenstance of difference is in melanin, making us feel separate in some way, making some of us feel separate in some way, and the Sahara being a actual physical gap. And I was thinking about this in relation to the very long standing debate on the idea of black Egyptians and how many, many scholars in Europe, essentially for racist reasons, were denying the idea of black Egyptians for a long time. And then in the late seventies, you had people like Henry Louis Gates talking about black Egyptians, and then you had people saying, no, they weren't black Egyptians. And they were talking about DNA. And all of this debate is essentially false because melanin does not define humanity. And the idea of it being a separate group around the Mediterranean, being separate from southern Africa is is is entirely a false perception. And I want to think you to think about how people moved through Africa and the importance of the Nile River. If you look at the cradle of humanity, you look at you look at East Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, up into Ethiopia, you'll see the Serengeti where we evolved, where we learned to throw stuff at other stuff and became big brained creatures and developed tools. That's all sitting just south of the Sahara with the Nile River running from Sudan north across the Sahara directly to Egypt. And that is the that is that is the trunk of the tree of humanity is the Nile River. It is how we moved up from Africa through Africa and able to move into the northern shores of Africa and along the Mediterranean. And then from there, essentially right through Israel, Middle East, you know, the places we keep on bombing each other in Gaza, that that is the connection right there, Gaza. And it's it's bizarre to me that we are constantly fighting in these areas, just like when we are in Iraq. And I realized it was between the Tigris and Euphrates where we're bombing Eden, you know, now now we're involved in the main way. We as a species move. We're bombing that place. Gaza is is where this connection is. And it's it's it's just horrific to me that we even see ourselves as separate peoples in any way because those are all physically connected. And so if you…

Eric 8:20

Physically…

Dr. Josh Stout 8:21

Physically connected and really not just incidentally, but primarily through the Nile. And so you have people like Cuvier, the 18th century French scientist, trying to argue that Egyptians were Caucasian. You have lots of arguments back and forth for a long time, 19th century. You've got people saying, no, they maybe they were they were black Africans, and it was all about race and pigmentation and never about the idea that, of course, there is this this connection between Southern Africa and everything else via the Nile, and that Egypt was really central to our our motion as a species growing up and and spreading out of out of Africa from Africa, that these are basically one solid conduit. And if you look at it, if you look at the pictures of the Nile, you can see this green band running up through the Sahara. And so Egypt was never a separate place. It was always connected. The Egyptian empires went all the way down to Sudan. There was there was dynasties from Sudan who conquered Egypt. It was always mixed back and forth. The idea of Egypt not being African is crazy. It has always been a African civilization and it's always been the cradle of humanity. So our roots might be, you know, further, further south in Kenya, Tanzania. But as we started to move, as we started to mix together, as we became humans, we were always traveling up and down the Nile. Around 400,000 years ago, there were separate populations in Africa, So there was groups in there was groups in Morocco who were developing the rounded skulls that modern humans have. We have a very round skull there were groups in closer to South Africa I South Central Africa, where our X chromosomes developed. So obviously the X chromosomes we have have to be part of the same humanity that has the round skulls, but they've developed in different parts of Africa and then mixed together. Our Y chromosomes come from still another part of Africa and obviously the Y chromosomes in the X chromosomes have to be part of all of humanity together. So this movement up and down through humanity is how we became humans. It was taking occasionally isolated populations, groups of genes that they would develop that had advantages in that isolated situation. And then during periods of warming, particularly the Eemian, Interglacial, you know, around 300,000 years ago, these were times when all of our populations would grow and they would mix together. And then when it became colder again, we would be isolated and develop specific genes. So these periods of time during the ice Age, we as a as a species, as as a genus, homo, homo, homo, Homo Erectus, homo Neanderthal, Homo sapiens, all of that was being put together in the in the middle Paleolithic because of climate change, because it would get colder, the Sahara would get bigger populations would get isolated, then it would get warmer again, the Sahara would bloom and we could move through it. And so this is this sort of cycle of of colder to warmer to colder to warmer that isolated us. And then mixed us together. And when we were isolated, we would get down to very low numbers. It's amazing we survived as a species.

Eric 12:04

But when you say we were isolated, you mean there were pockets of proto humans?

Dr. Josh Stout 12:10

Photo Humans. Archaic humans that.

Eric 12:12

Were existing contemporaneously, but isolated from each other.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:17

From each other all over Africa. Yes, North Africa, South Africa. And then during times when things were great and the Sahara was a beautiful grassland, people would move around in these paddocks together.

Eric 12:28

And how much time was between these these epochs?

Dr. Josh Stout 12:32

I guess the interglacial is might last a few hundred thousand years.

Eric 12:36

So it was long enough for actual evolutionary changes to take. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:40

So if you think about the, the different ages of the Paleolithic, you have the, the lower Paleolithic known as the old Stone Age in Africa and this was when we were first developing big brains and some of our simpler tools, the hand axe Middle Paleolithic is when we start getting spears and we start getting more abstract thought. This is the time when the the characteristics of modern humans are starting to develop. Somewhere along the lines we get a chin. We still don't know why we got a chin.

Eric 13:11

But you're saying that this is all part of having been coming together and then being isolated from each other and having time to evolve separately and then come back together and mix that DNA again.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:25

And going through very, very small populations. So we were we would get.

Eric 13:28

We were weeded down very much.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:30

We got weeded down, down to a few tens of thousands of people periodically. And so we became very homogenous because of this. Whenever we would mix together, there was only a limited population that became almost completely homogenous. And this is one of the points I wanted to make of how not different we are from each other. Yes, we groups of us evolved separately in different places over hundreds of thousands of years, but there was always this mixing together and homogenization as populations crashed and it was one of these tiny sort of splinter populations that was able to go across, you know, the Sinai and get to the Middle East and then was able to spread out, interbreed with Neanderthals and then spread out across Europe.

Eric 14:15

And kill everything else.

Dr. Josh Stout 14:16

And kill everything else, including Neanderthals. But that's our history that we we always competed with, you know, the other people we would meet and then also interbreed with them. And so that that is absolutely part of our history. But going back to the idea of the Nile as connecting the the Mediterranean area with the the southern African area, it really fundamentally shows Egypt as a African civilization and that all the arguments over whether it was black or not is immaterial. I was actually I remember being an undergraduate and some of the sort of late eighties black Egyptian stuff was happening. And I was somewhat bothered by this because it seemed like full scholarship. And I think it was I mean, if you if you if you go to the Met, you can you can you can see they they depict people from Ethiopia with a darker skin color than other groups. But all of that was meaningless. And what I wasn't realizing is the people who were saying, look, the Egyptians were a, you know, a black African group. While they might not have been correct about skin pigmentation, they were correct about fundamentally understanding Egypt as an African civilization, and that this is what the modern scholarship is now saying is that there were a variety of different pigmentation levels and types in North Africa. This was the population's mixing around, this was what Africa does is it takes populations and it mixes them as they go along these river valleys. There's places where everyone has to come together as they're traveling north. There's only one way through along the Nile, and then they spread out again. And so you have this bringing together and mixing and then spreading out and that this was specifically happening in Egypt.

Eric 16:09

Which and you're also saying this was happening long prior, this exact same thing had been forced upon us by geological and environmental situations.

Dr. Josh Stout 16:18

Yes. Yeah. And it really only has been about 600 generations since the end of the Ice Age. So we've we really haven't evolved much since then. There's been very, very little change and that we're essentially an entirely homogenous population now.

Eric 16:32

We're now we're not in a in a position to be isolated at all.

Dr. Josh Stout 16:35

Well, now now we're moving around a lot as well. But I, I think I've said it before, but I really like the the example of a chimpanzee from the eastern Congo is more genetically distinct from a chimpanzee from the western Congo than a human from, say, England would be from a human from Papua New Guinea of the un-contacted tribe in Papua New Guinea has more in contact, more in common, sorry, more in common to see me than chimps from the other side of the Congo. When we think of chimps is exactly the same, we don't think of different races of chimps. We really? Yeah.

Eric 17:15

No, we don't.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:16

We really don't. And they're more genetically distinct than then groups of humans are. And so this this is just all this huge fallacy that has been with us for a very long time by the the the accident of history causing differences in skin pigmentation and our perception of the Southern African groups being somehow cut off from what's happening in Northern Africa. And that that's very much not true. The Nile River runs right through it. And there's always been a continuous genetic flow back and forth and continuous cultural flows as well. And so there's there is no separation. And that anyone trying to say, oh, you know, European culture has this origin in Egyptian culture. And there therefore is this, this, this North African thing that's somehow superior to what was happening in Southern Africa is is nonsense.

Eric 18:09

Yes, well, there are all sorts of people trying to rank civilizations all over the place today. But I think that, you know, part of of what Robert was getting at.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:22

Yes.

Eric 18:23

Was our you know, our need to be aware that the language that we use is rooted in an era where there was no other language to use. But now there is. Yeah, we didn't know, and we were raised by people who had no perception of what we understand now.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:47

But I mean, also, I think I think it is technically correct to say, you know, we as a species left Africa like we as a species crossed Africa on the Nile. We as a species has moved apart and come together. Yeah, exactly. So I think it is.

Eric 19:06

We as a species spread. We did not leave. We spread.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:07

Well I mean some of us left.

Eric 19:09

Some of us left, but not all of us left.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:11

Right. Yeah. So these are indeed important, important distinctions.

Eric 19:16

But they are also completely fed by the history our, ours, our, the history of humanity that I certainly don't know. Yeah. These, these things, these things inform this.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:30

Yeah. And it really became important for Europeans in particular to try and separate themselves from Africa once scientific racism started happening. So you have, you know, religious based differences between groups, you have cultural based differences between groups. But once you get into the age of reason, that's when Europeans in particular started getting really nasty.

Eric 20:01

We will weaponize anything we can.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:02

And becoming a justification for slavery, colonialization that not not just a justification, but a mandate for these things because of our somehow superior natures, which was always entirely false. I mean, certainly the Egyptians would have never even imagined these ideas. They would not have seen themselves as separate from any other group because they were physically connected. And they'd always seen, you know, there was differences between, say, the Upper Nile and the Lower Nile with with, you know, say, the the the origin of the Jewish people with the Hyksos in the Lower Nile and the Upper Nile being closer to Ethiopia.

Eric 20:42

This is what bothers me with the concept of American exceptionalism.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:46

Yeah, we are We are not different people.

Eric 20:48

I … just we're not. Yeah. Yes. And it's yeah, I feel like it's all coming from the same place.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:56

And it's also something that makes, you know, America wonderful is our ability to be a group of different cultures coming together. And, you know, if we want to look at historical precedents, we should maybe not be looking to Rome, maybe we should be looking to Egypt. We should be looking to a place that wasn't out conquering the world, but a place that was mixing peoples and a place that was building culture over a very long period of time and developing the principles of of of mathematics and the principles of how how we understand the world around us through observation of the Nile flooding. We understand how the stars move through the sky. We can predict where where the seasons are coming from. All all of this is coming directly from the Egyptians through the Babylonians to the Greeks to the to the Jewish peoples who were developing their understandings of the world. Monotheism coming from Egypt to the Jews. All all of these concepts are directly rooted in Africa. They are from Africa, but they are African, you know. So, so. So when I say we came from Africa, these are African people who came from Africa. That's that's, that's what I'm trying to get at. Now, there are racists out there who like to say, Well, since we're all African, I can't possibly be racist. I'm not saying that. All right. There are. There is. There is. There are certainly African cultures that have their own histories in African cultures. There are certainly European cultures that have their own history and their own their own cultures. They're not exactly the same things. But what I'm trying to point out is this real through line, through Egypt and through the Nile crossing, crossing the Sahara, and how there is no break. There never was a break. There's no separation.

Eric 22:56

There was also no other way.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:58

There is no other way. Exactly. The only path and the the the the the the importance of both Egypt and where Israel is as well historically. And that this was the path to the Fertile Crescent. This is how we got to these places and how we developed civilization itself was from this movement from from from Egypt through through through the Fertile Crescent, through developing agriculture. You know, Africa doesn't have its own breed of cows. I mean, course, Africa has its own breeds of cows. It doesn't have its own genetic lineage. Of course, there's two genetic lineage of cows in the world. Well, that's not true either. There's two main ones there is. There is. There is the the European cows boisterous and there is the cows from India, both indica. And these populations actually were coming the other direction. So those two populations mixed in North Africa, in Egypt, people taking those cows in Egypt, the Egyptian cow, half or that major aspect of their civilization essentially represented civilization to the to the Egyptians. Those were the cows that moved south along the Nile and became the cows that the Maasai in in Kenya, Tanzania are. They're they're herders, they're pastoralist people. So the people who are now living where humans evolved are also directly connected to what is north of out of north of the Sahara. There is no separation. The cultures move both ways and they really always have. So if you look at, say, the, you know, fantastic cows with the giant horns from like Zimbabwe or something like that, and you think, well, these are these are clearly African cows. They are clearly African cows. They've been there for thousands of years. But that's thousands of years. That's not millions of years. These are mixes of European and Indian groups that have interbred and formed these unique populations in southern Africa.

Eric 25:06

Having met in Africa.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:08

Having met in Africa. Yeah. And probably having met in in Egypt first. So the first the first cattle in Egypt are shown to be there. They're both boisterous, the European cattle. But then very quickly you start seeing influxes of the the Indian cattle, the the cows from India tend to be more resistant to diseases that are common in hotter climates. So they had useful genetics. And people recognize that early on and the groups were being interbred.

Eric 25:46

I've always said mutts are the strongest and the smartest.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:48

Well, humans are only mutts. We don't have any purebred anything and really never have.

Eric 25:55

And I love that there are so many people out there in the media that would disagree with that treatment.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:01

Well, they are. They're just so fundamentally wrong. And, you know, while science has a lot to answer for in its defense of racism and slavery and colonialism, the nice thing about science is when it meets facts, it can at least slowly start to change its mind. If you have, say, racism based on religion, it's much more difficult to be flexible in response. But when you start meeting, you know, new ideas, science has a little bit of better ability to to to change its mind. Now, often you have to wait a generation. The people who are existing today might not be able to change their mind.

Eric 26:41

Yeah, well that's that's, that's that's deeply frustrating because a generation is my lifetime.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:47

Yes, exactly. No, no. We never move fast enough.

Eric 26:50

I'm so sorry. I'm so sorry for the noise outside, But let's. Let's continue anyway.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:56

Okay? I can't even think at this point. Yeah. All right.

Eric 26:58

There we go.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:59

At least we seem to be over it. Yeah. Yeah. So I just want. I just wanted to talk about that and say that I, you know, I apologize for any any mis phrasing to see think that humans as a group somehow left Africa and weren't there anymore, but.

Eric 27:14

That or that there were two groups.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:16

Or that there were in any way.

Eric 27:17

To any in any way.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:18

In any way to groups. There's only one group of humans and always has been one group of humans. And that that group has has a direct connection along the Nile through Egypt and then right into the Middle East and then spreading out from there. And that it is always been connected. There was never a disconnect. There's never been a time when it wasn't connected. There's always been through lines of of genes and animals and, you know, creatures. Are there any chickens in Africa? Yes, there are chickens in Africa. Where did those chickens come from? They come from Malaysia. It's there's always been things spreading along these these trade routes. Now, they're also coastal routes as well. But those would have been happening much later. Humans weren't very good at boats at first. So follow It's following the rivers across across the Sahara would have been the way and very specifically the Nile.

Eric 28:13

But but but but again the the the in your you're you're putting Africa not just as the cradle of humanity, but the cross roads of humanity for thousands of years.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:26

Yeah, absolutely absolutely. And that you know the real only difference that non sub-Saharan Africans have is is the slightly larger amount of Neanderthal genes, you know, one or 2%. But if you think about what makes us truly human, every everything that makes us truly human evolved in Africa in one of these populations within Africa, from our reproduction to our brains to our language capabilities, all of these things are in Africa, and all of them were very heavily selected for the genes we got from Neanderthals are only things like skin color and hair. They're they're superficial. Couple of couple of them might be slightly less superficial, such as our immune systems. It seems as though a lot of our autoimmune diseases might be a heritage of the Neanderthals. If you're moving into a new area, it the genes you want to pick up are the ones that, you know, protect against the diseases in this new area. But you don't want to get rid of your superior language abilities. We were able to outcompete the Neanderthals probably because of our imagination and our ability to to speak the way we do. Neanderthals undoubtedly had language. They even seem to have, you know, the beginnings of of cultures. But it wasn't really until they encountered us that they were able to do anything like art or their more advanced tools. That was after they interbred with us. First time we left Africa. I don't think we survived. I think the first the first group was about 100,000 years ago. Again, I'm talking about us leaving Africa, but definitely we're still in Africa. But that first group was wiped out about 100,000 years ago. However, genes moved into the Neanderthals, which they took up. So we never took up any Neanderthal brain genes, as far as I can tell. But they took our brain genes, so they suddenly were able to do things with their art that they hadn't what? They hadn't had art until they encountered us. So they start encountering us. They pick up some X chromosomes from us, they pick up some mitochondrial DNA starts going into the Neanderthals. And so at the same time, I suspect that they were getting the ability to do the advanced tools and the art that they acquired around that time. When we finally survived around 60,000 years ago, that was a group of of probably less than 10,000 people who were crossing from Egypt into the Middle East. And they were a very small, very homogenous group of Africans who then were able to interbreed with Neanderthals and then eventually push them out, taking only a tiny bit of that Neanderthal DNA with them. And that's the only thing that you could say genetically separate that group from sub-Saharan Africans. But even even those people, once they developed agriculture, that.

Eric 31:15

If you can go one way, you can go you can go the other way.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:17

Other way. Exactly.

Eric 31:17

It can't just stay in one place.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:19

Exactly. So those genes came down with the cows.

Eric 31:21

And that’s what you’re saying… and these and these these these became routes of trade for millennia. It's not exactly thing that can. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:29

So so, so so with the cows and with the chickens we also getting a little bit of Neanderthal DNA coming down into, into into into sub-Saharan Africa.

Eric 31:40

I have to apologize for living in Manhattan. Upper Manhattan.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:43

Yeah, I think I'm done now. I can't talk anymore anyway.

Eric 31:46

I just want to. I just want to thank Robert for A) listening to all of all of this all the way through more than once, and also for for bringing this topic up because I it's important and and we I really want you know what you're saying to be to to be received some in some form in the way that you intended to be received.

Dr. Josh Stout 32:09

All right. Thank you so much.

Eric 32:10

All right. Thanks, everyone. Until next time.

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa

.jpg/1200px-Painting_of_foreign_delegation_in_the_tomb_of_Khnumhotep_II_circa_1900_BCE_(Detail_mentioning_%22Abisha_the_Hyksos%22_in_hieroglyphs).jpg)

.jpg/1200px-Gorgeous_Green_along_the_Nile_River_(MODIS).jpg)