The Non-Science of Individuals

Science can only look at groups - but only individuals exist. Today Dr. Josh stout discusses how we can see the individuals, and why this is vitally important for climate, ecology, biodiversity, medicine, and in our own daily life.

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:00

This was something that I wanted to just sort of talk about because we we so often associate science with any lack of connection that science can say what a flower is but can't say it's beautiful. And that idea of appreciating the aesthetics of something is very much appreciating something on the individual level. And that's something that I think is difficult for science to do because you can't get a number for it. But it's the only way to really understand things. And I think it's possible to do within the realm of science just the way it's possible for a doctor to treat you as an individual within the realm of being a doctor. It's just hard for some of them.

Eric 0:47

Friday, June 7th, and I’m sitting here with Dr. Josh Stout. Good morning, Josh. How's life?

Dr. Josh Stout 0:55

Good morning, Eric. Yeah, things are good. I'm on summer vacation, which is now going to get everything chaotic again, so we might get off schedule. So I thought I'd do two episodes today and I wanted to start off with thinking about how science can address the concept of the individual. Both for humans and in the animal kingdom, because we only exist as individuals. But science only looks at things, you know, is it statistically significant? Is the is the treatment group, you know, have a higher mean than the than the control group? It can only look at aggregated numbers and make decisions based on aggregated numbers. You know, this was what you know, Asimov's Famous Foundation series I talked about with Hari Seldon and Psychohistory.

Eric 1:51

Oh, I loved that when I was 14 years old. I loved that so much.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:55

And the economist Paul Krugman talks about the ideas in the foundation influencing his work that led him to a Nobel Prize in and that looking at yes, the ways yes, the ways the world moves as large groups can give you tremendous predictive power. And so, you know, I'm interested in the way we can see the future through demographics. I'm interested in looking at how how, for example, you know, most medical science is based on large double blind tests where in the trials where you really get great answers, if you have 50,000 people doing something and this is this is how how we learn things. Yeah. And you have to do it with these large enough.

Eric 2:49

I just have to say, though, that the people who are influenced by foundation were influenced by the books. Oh, yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:56

Not. Not that show. TV show. No. They did a weird remake of of episode four of Star Wars.

Eric 3:02

We don't we don't we don't need to geek out on that.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:05

But they had a Death Star anyway.

Eric 3:07

Yes. Moving right.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:08

Moving on.

Eric 3:08

Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:09

But yeah so so the other book he was influenced by and one that influences me to geek out on these things is is Dune and so looking at ecology.

Eric 3:20

Oh Frank Herbert.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:21

Herbert Yeah well certainly Dune one was was amazing and, and the movie there are quite good but the idea of of looking at entire planetary ecology I'm sorry to make predictions.

Eric 3:32

I'm sorry I have to interrupt. You mean you mean the movie. The movies are quite good. The new ones as opposed to the original ones which were terrible, doesn't exist, as you know. Usually it's the other way around. Yeah. Anyway.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:44

But the idea of of again, looking at large areas, large movements, you can start to make long term predictions of something like global warming. We can actually see what's happening on a planetary scale. Doesn't mean I can tell you when it's going to ring, you know. But but what it's going to rain is the only thing that matters to us. Yeah. Yeah. It's only the individual occurrences that actually matter. And so you can make sort of large scale predictions of summers will be hotter, winters won't be as cold. We're going to have more droughts, but also more rain and more wind. But I can't tell you when any of these things are likely to happen. And it's the same thing that doctors are working with. So when they have all this medical information, yes, they then have to tailor something to an individual and the information they have isn't built for that. It wasn't made to work that way. They can't know anything because one data point doesn't give them enough information. So they can only work on sort of large scale hunches that were built on tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of people. And you're a single individual with your single set of stuff. Your organs aren't even in the same place as everyone else. Everyone's a little bit different. Your nerves are slightly different pathways. Everything is more or less the same.

Eric 4:57

I'm sitting here smiling because again, I have to bring up my doctor who was specifically. He was like, okay, you're going to go on the Internet and you're going to see that with these test results that at a population level you have a very low risk. But we're talking about you and you're an individual. So I want you to stay on these drugs. Yeah. And he made a distinct he he went right to what you were talking about.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:21

Well, I often I often think about it a lot like cooking where there's a lot of science involved with cooking the fats, combining with the proteins and the proteins combining with the sugars, all of these things. Health really well identified sets of characteristics that can give you predictions about how things will work in cooking. Well, you don't really need to know that part as well as what you need to know when you're working with a particular dish, an individual dish, when you're working at the individual level with this stuff, you're kind of guessing, you're adding a little bit more salt, you're adding a little bit more of of of garlic. If you look at the clove of garlic, you're not measuring it precisely. You're just saying I could use two of those. And that's how doctors are treating us. And good ones are like, good cooks. They're they're using what they know about the science of cooking and then the kitchen, and then they're trying to bring it into, into, into a into an art form.

Eric 6:20

Yeah, yeah. Every, every, every meal. You can make the same recipe on two different days. It probably will not take exactly the same.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:27

My kids ask me how to make fried rice. I'm not sure I can do that. So I actually what I did is I took my ingredients and ran it through ChatGPT. And ChatGPT. came out with a standardized version of Fried rice, which they then made last week, and it tasted like my fried rice did what I first started. It copied a cookbook and it was amazing. I'm like, Oh, I remember this. And I haven't made two. Fried rice is the same since then.

Eric 6:54

Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:55

But they they went back to the beginnings, which is why I did it that way. I said, This is a blank sheet that you can add everything to, but if you make egg fried rice, you'll, you'll, you'll know how to do things in the future. Like I gave that sort of here's a standard. And that was, you know, ChatGPT. was great for coming up with a standard like that again, turning something into a sort of a standardized, generalized approach. And then you try and make individual versions of it. And so, you know, that's what I'm trying to help my children when they're when they're learning to cook. But this is what absolutely doctors are doing. And I wanted to think about it in terms of the natural world as well. This is not something where it's easy for us to conceive of animals as anything other than all the same. If you look at a sparrow, that's an individual sparrow. You can't tell it apart from all the other sparrows you see.

Eric 7:44

I can with dogs and cats, but not with not with birds in a park. No, that's.

Dr. Josh Stout 7:50

That's actually one of the things about pets. And it's a good point. Pet pets are individuals to us. Animals are not individuals. Yeah, pets have personality. They have reality to us. They're members of the family. We worry about them. If we don't see them for a while, then they come back. We feel relief, all of these things. Whereas if there were one sparrow you didn't see that day, you wouldn't know and you wouldn't care. And so that's how we feel about the natural world. So if you see a 10% reduction in birds across the board, you're like, oh, less birds. Yeah, they're not those are not like one in ten individuals has now been killed.

Eric 8:32

Which you don't know. You don't, you don't see it as a decimation.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:34

No. And that's actually that's, that's way too optimistic. It's more like half, half in the last 20 years.

Eric 8:41

You, you're actually saying right now that we've lost half of the birds. Yes. In 20 years.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:47

Yes. And we haven't noticed.

Eric 8:49

It all birds.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:49

Yes. I mean, it's not all.

Eric 8:51

Have you mean globally or in cities or.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:55

Europe and the United States in developed areas. And it's sometimes 90%, sometimes it's half. Sometimes it's only a third. So like half. But half of Blue Jays, which have been doing really well, half of Blue Jays are gone. Even even starlings are down by like 30%.

Eric 9:12

What's happening?

Dr. Josh Stout 9:13

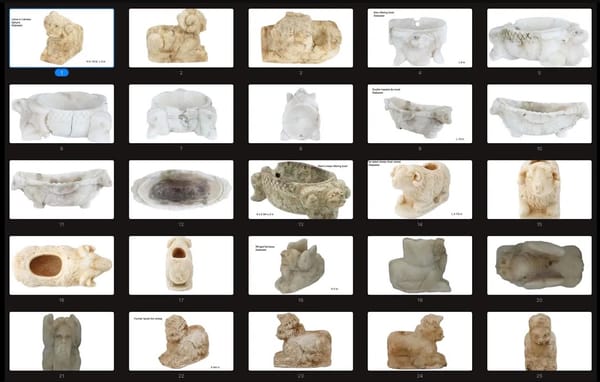

Warbler is maybe 90% mixtures of pesticides, habitat loss, all the bad things that are difficult to just do. Like we can't just protect them as individuals. If you want to just focus on I'm protect this one woods, for this one bird here, you can probably keep that bird alive. But if you don't focus on them in that way, you can't keep them alive. Actually, it's really interesting. There is a pro hunting organization, Ducks Unlimited, that has pushed in a really bipartisan way to protect ducks. Ducks have not gone down in levels. We still have the same numbers of ducks we had 20 years ago is everything else is all of the songbirds, all the perching birds there, there, they're way, way down. And it's because we've had this really concerted effort to save this particular wetland, because that's where I hunt and this particular other wetland. And if you're going around shooting birds, you actually start interacting with them much more as individuals. And so you care about their particular spot, not just in general. We need to protect wetlands. I need to protect this one so that I can hunt there and that works. And people have actually been quite successful at protecting the ducks because they think about them in a different way and they end.

Eric 10:34

It's because they think about them at all.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:35

Because they think about them at all. And and it's able to cross the partisan divide. If you can't get both Republicans and Democrats working on something these days, you can't get anything. And we don't agree on anything. And so protecting ducks was one of the few things that everyone kind of agreed, you know, from from Dick Cheney with his shotgun, you know, shooting people and ducks to everyone else. We really like her, but apparently we don't like warblers, for example. So.

Eric 11:04

Well, is it that we don't like them or we just don’t think about them.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:06

We don't like think about it. We don't care. As long as there is some birds out there, they're all the same bird to us. And so, you know, we prefer to have big hotel complexes on islands in the Caribbean where these things overwinter. And so now they have no habitat anymore. And we put a various housing complexes, you know, right at the edges of woods. So now that there's no unbroken forest, so that the, you know, the brown headed cowbird goes in and out-competes them. And so they they have their nest parasites and it only happens if there is, you know, grassland next to the woods. So someone's lawn allows these other birds to go in and outcompete the warbler. So on many levels, these these birds are just not being thought of. And we need we need to think about that as individuals. We think about our own health, and then we sort of worry about the health of our society as big numbers. But, you know, this this is, I think, in many ways how we need to think about, you know, working with each other, building communities, acknowledging that these people are individuals. It's, you know, with with with the various wars going on right now, when you hear about them as generalities, you're like, oh, that's bad. But when you see someone who looks just like your kids, who's just been bombed and you say, oh my God, this is these are individuals who are actually suffering in this way, It becomes much more acute.

Eric 12:36

Kind of the story of Vietnam, wasn't it? In many ways, the first war where we had some of those pictures saw.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:43

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And I think it's something that we really need to to work on on many levels. And I, I wanted to tell some stories about sort of individual animals. I have I have met as I go out on my porch every morning and I meditate for, you know, roughly half an hour or so, some sitting, some actual meditating. And I try and be aware of the world around me.

And so I'm aware of the birds and the squirrels. And I start to realize I'm seeing the same birds and the same squirrels and that those are not just squirrels in general, but that's a particular squirrel and that's a particular bird. And I've started to try and interact with them on that level.

The first one was probably the most profound, was I would just go out and I would I would sit and I would listen to the birdsong. And I heard this one that I just thought this was how birds call. But it was it was amazing. Why did no one know that there was this bird out there that could compose a symphony that would last ten, 15 minutes of solid like composed through line, like story it was telling. And then after two years, I didn't hear that bird anymore. It was gone. And so I realized what I'd been listening to was a white throated sparrow that was the equivalent of Mozart.

They they they actually grow a bigger brain every spring as they get more testosterone. So the males start calling and they they grow a bigger brain over the same part that humans have for language. So it's the FOXP2 regions. So these are these are regions that are not just producing sounds, but they're interpreting and changing sounds. They're not like a stereotypical frog call. These are the same regions that control, say, a whale song or something like that. So these are communicative patterns that have meaning for the birds. They're they're not just a stereotype. I sing this way, but if you listen to a white through a sparrow, they have a very stereotype call and it's very simple and it lasts about 15 seconds. And so I was listening to something that was able to carry a through line over over ten, 15 minutes at a time.

Eric 15:10

How did you know it was a black throated sparrow?

Dr. Josh Stout 15:11

White, white throated sparrow.

Eric 15:12

I'm sorry, white.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:13

It's about because of because of its call. It was still using that same that same call. I don't want to whistle it to them.

Eric 15:19

No, don't do that. We'll we'll we'll post the link.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:21

You know, it's like I. Dee dee dee dee dee dee dee. And that's it. That's the whole call. But this thing will go like dee dee dee dee dee dee dee. And then like expanded over over long periods of time. Dee dee dee dee dee dee dee dee dee. But better than me, you know, I hope. Yeah. Sorry. I mean, like I'm trying to give an example of how would you like you knew what it should be doing and it was doing something else like jazz, but it was like if jazz were done by Philip Glass, it was very slow and minimalist over this very long period of time with huge gaps. But it was it was like counting. It knew how long the gap was. So it it came in on the right beat when it came in with the next note. And so I thought that this was how all white throated sparrows were that no one had ever noticed before. And then I realized it was this individual sparrow. And then when it went away, I was I was it was a tragedy. And it was in a world where, no, I could explain this to no one. Like, you know, it's like we'd lost a Mozart and no one had even noticed. And I wondered a lot for it that we needed to figure out which bird it was. I forgot what bird, what birding was. And then I started listening for them. I'm like, Do they do this? And they actually do get better. They in February and then they get better over the course of the spring as their brain gets bigger and they get practice and they they hurt other birds. And I do hear them get better at it and they'll get to where they actually go back and forth. They'll do a call and response. So if one goes. Dee dee dee dee dee dee dee. And so they're remembering the calls and then playing them back to each other. But this one had had figured out how to do it with himself. He was able to remember his call over a long period of time and then relate to it when I'm when I'm up at the in the country in Stillwater, they'll be larger groups of white throated sparrows because there's more sparrows up there and because it's quieter so they can talk to each other and I'll hear them doing something closer to us. Symphonic experience where they'll hear sparrows on one side of a lawn talking to them on the other side, and the blue and further away, and they'll all be in a conversation back and forth. But it still only lasts three or 4 minutes tops. This this guy could go ten, 15 minutes. I was I was just blown away by it. And I, I don't know what to say other than it was a brilliant individual Sparrow. And we don't think about them that way. We don't think about sparrows that way. We don't think about birds this way. And if we want to protect them, this is how we need to think about them. You know, I saw this as a tragedy. What happened to it? Was there a cat? What could we do to stop this ever happening again? But these you know, these are these are these are difficult things to think about when it's all just birds.

Eric 18:23

Mm hmm.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:24

I've had I had similar relationships with individual birds since then because I realized I could. So there is there's they've gotten rid of some of the stray cats, which is good for the birds, but it means the rats come in. So if you feed the birds and you have bird seeds, you have rats coming in, so you can't feed the birds. So we've been feeding the birds. Now we had to stop feeding the birds. And so I started feeding individual birds.

And so I would go out and I would put a couple of bird seeds on the railing directly in front of me as I sat, meditated, and I was not doing it for birds in general. I was doing it because I knew a bird and thought I could feed him. So over the course of prior two years, I'd been watching this cardinal and so we had a male and female living in the bush, you know, near near where I sit on the porch every day. So I watched them raise this this young male cardinal, and he was well fed. His mom and dad fed him all the time. He got bigger than other male cardinals. He was fatter.

Eric 19:30

You were watching this process.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:31

I was watching this process and he was super lazy. I watched him sit as a fully fledged purebred cardinal male, cardinal, adult sitting on a bush full of red berries. And his father would land in front of him, pick a berry in front of his face and put it in his mouth. For him.

Eric 19:50

It's just it's so hard to believe that that exists in the animal kingdom. But you saw it yourself.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:56

Ab-so-lutely it does. And so my cat at some point grabs the father. It's tragedy. I get the father away. You know, the cat did not kill it. The father flew away. I saw it over a couple of future days. It moved first. First it moved, and then his wife moved me to whatever. Yeah, It's hard when you start seeing of individuals. It's hard not to think of them. They're like, tight paired kind of stuff. And so I knew where they'd gone.

But his son stayed and they tried to come back and get him to move, but the son stayed. And the son, because I've known the son his whole life, the son had known me his whole life. And so we sort of recognized he would come and he'd chip at me and yell at me for being out there like he'd chip at a cat, but a little less aggressively. And so I'd be sitting out there and he chip at me every morning. So I finally said, You know, I'm just going to see if I can give him some seeds.

Eric 20:55

So the seeds were for this one.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:57

Yeah. So I knew him ahead of time, put the seeds there and then would sit and meditate. And after about two weeks he was coming out and eating the seeds. And so now he calls for me. He goes, Chip, chip, chip. And I come out and I put the seeds down and I'll sit with him. Sometimes I'll do it more than once in a day. I do it every morning guaranteed. But if he comes in, wants other food, sometimes I'll do it. So I'm giving it to him personally. His his. His mate does not like to come down, so she sits up there. He carries the seeds up for cracks them and puts them in her mouth.

So he learned from his father how to do this. And now he's treating his mate this way, which is lovely. And so he's very affectionate, he's fat, he's getting a little bit he's having a hard time as a dad. He's doing a lot of work. He looks a little beaten up. He's missing patches of feathers here and there. Wow. I look you look a little bit scruffy. He's not as sleek as he once was, but he's still bigger than the other other cardinals out there. And he's still the one I'm coming to you.

There's now a blue Jay that has started following him around, kicking him out and stealing his his seeds and this particular blue Jay. And I think I know which one it is. I'm not positive. But about four years ago, while I was meditating, there was a family of Blue Jays that had just hatched and they were basically everywhere in the yard. And one of them was wearing a blue shirt and it came and leaned forward and was begging for food for me because I thought I was a giant blue jay and I knew I couldn't move. And as soon as I moved, it was really upset because I fooled it into thinking I was a blue jay, and so it was angry at me. And so every day for four months after that, it would bring its whole family to see me and yell at me.

And they would all just sit in the in the tree yelling at me. And then after a year of this or so, they were they've gone from the really aggressive call, the blue Jay, to the less sort of aggressive whistling calls. And then it was just him. His whole family wouldn't come anymore.

Eric 22:54

They got tired of this.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:55

They got tired of us. But he stuck around in the neighborhood. So I think it's that blue Jay that is now coming for the food as well, because he's known me his entire life.

Eric 23:03

He's not just coming for the food is taking it from…

Dr. Josh Stout 23:05

From the from from the cardinal, but also because he's known me his entire life. And so he's comfortable with me. And so I always make sure I take in the cats when I'm out there, if I like if I meditating, there's going to be no cats now, other times a day. I can't guarantee that. But if I'm out there sitting no cats and so I don't know what they know, but they they sort of have this relationship with me that I have now built. And so if you start seeing what's in your backyard as an individual, it's very, very different than when you see them as just groups of birds. And it does matter. You really do have to pay attention. And this is happening all the time. It doesn't have to be sitting there looking at it every single day. You can have moments where you're noticing something is an individual, you know, just once, you know, when I was a kid, there was a blue Jay that lived outside my my, my bedroom and a tree right there. And I didn't really think about it as any particular blue Jay. But it was you know, there was a blue jay. They lived in the tree there. And one time there was a probably a Cooper's Hawk was chasing it, and it flew right at my bedroom window. And then at the last second, pulled up and the Cooper's Hawk slammed into my window. And the blue Jay sat in the tree and went, Oh, you know, that was a very individual moment. That was a thing that that Blue Jay had figured out that not only did it have a tree, but it had a window that was invisible. But it knew where it was.

Eric 24:39

It knew. Yeah, exactly. That's great. Yeah. I mean, I had I had a similar experience. It was not nearly as involved or complex as your your. But I was at Marcy campsite once and a bird came hopping over begging for food, and it actually popped up on my hand. Okay, great. You're. You're familiar with people. But the next morning I come out of my tent and I'm stretching and I stand up. I've just been sleeping on the ground and a here and the bird lands on my shoulder. I got the the seeds and I fed it from my shoulder. But it had to be the same bird. Yeah, I knew. I knew. Even though it was the second time I had seen it, that it was the same bird.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:20

Yeah. Yeah. No, it was, it was a I wish I could remember people's names.

Eric 25:26

As individuals.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:26

Well, the way I remember other things.

Eric 25:28

Somehow I completely accept this about you.

Dr. Josh Stout 25:31

But it's just something I can't do. So anyway, there was a famous actor that anyone would know the name of. Yeah. on Colbert’s show, and he and Colbert was like, So you're you're old. You used to have a reputation for partying. What do you do now? It's like, Well, I was just in Berlin and there was this bird who would fly up to me and I'd feed him every day. That's what I was doing in Berlin. I didn't go to any parties. I was in bed by 9:00. I was feeding this bird. And Colbert says, What kind of bird was these? And he looked slightly ashamed and I know why. And he looks down and goes, It was sort of like a chickadee. And I'm like, Huh? I know what it was, and I know why you didn't want to say it. It was a great blue tit. And that's why could they look sort of like chicken eggs?

Eric 26:18

He knew what it was that he was in. I think he did. But Colbert's show is exactly the place to say this exactly thing is true, that.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:27

He might have actually not known. It's also possible.

Eric 26:31

Well, there you go.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:32

But it would have been fun.

Eric 26:33

I mean, this is this is you know, this is the way I hope my doctor looks at me. I think he I hope he sees me. Is that individual bird? I don't know, because I can't imagine going every day seeing person after person after person. But you need to see them each. Well, I really salute individual.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:52

I recently had an appointment with a doctor and I realized that the conversation you have about your life with a doctor isn't just information so that the doctor gets information about you. It's also so that the doctor sees you as an individual, right? Yeah. And puts connections in with what you're doing in your life in general. And that is absolutely part of their their art. And if they can't bring out the individual in you, they're not doing their job correctly, then they should be having a conversation with you.

Eric 27:20

Yeah. Yeah. Well, like you said, each patient is like a dish you're making on that day. Yeah, yeah, yeah. What's the humidity? How many ingredients do you have? You have everything you need. Is it all there? Is it all fresh? Yeah. Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:34

Now, he asked me about my t shirt. I'm like, Funny you should say that. That's the orphic egg.

Eric 27:40

And away we went.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:41

Exactly. But yeah, so I just wanted to bring this out because I think it's important for us dealing with the medical system. I was thinking about the way we interact with science related issues and us interacting with the natural world.

Eric 27:59

Absolutely. Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:00

And that this was something that I wanted to just sort of talk about because we we so often associate science with any lack of connection that science can say what a flower is but can't say it's beautiful. And that idea of appreciating the aesthetics of something is very much appreciating something on the individual level. And that's something that I think is difficult for science to do because you can't get a number for it. But it's the only way to really understand things. And I think it's possible to do within the realm of science just the way it's possible for a doctor to treat you as an individual within the realm of being a doctor. It's just hard for some of them.

Eric 28:40

Yeah, I mean, what it is.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:41

That's being used.

Eric 28:42

What it is, it takes people who can understand, you know, across the boundaries of fields of of of study, fields of interest, of different, different disciplines. You know, it's fascinating. You were talking about having a having a lawn right up against woods can be invasive in the woods and can impact that that that requires that people who do urban planning understand climate science and social policy. And there's it's so it's it's it's fascinating and it also seems almost impossible and it would be.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:22

Very difficult because if you looked at that boundary between the lawn in the forest, it would be the most diverse spot. You'd have more birds there than in the lawn or the forest, but they wouldn't be able to breed successfully because they would be parasitized. So it looks like a great habitat. It is a great habitat to live in, but they can't breed it, so they need another spot that is deep in the forest where they're not going to get parasitized by the brown head of cattle birds. So you need you need to understand all of this stuff.

Eric 29:50

Yeah, it's immensely complex and also requires understanding much, much more than just the nature of the creatures.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:59

Right, right, right. This is this is what Temple Grandin was was doing when she was looking at slaughterhouses. So we certainly treat our food as every every animal is the same. We don't see them as having feelings and desires and pain and suffering and all these.

Eric 30:12

How could we exactly.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:14

Know? It's hard, but they definitely do. And they're all individuals, just like our pets. And they are the same in every way as us. And our pets in that sense. And so what she was trying to do was saying, okay, if we're going to eat these things, then we need to figure out how to minimize their suffering. And so you don't have a line of cows looking at the next cow getting slaughtered. You know, you you have to really make it.

Eric 30:39

So Josh is laughing at me holding my head. Yes. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:43

Because we didn't think of it that way. And it was horrendous for the cows realizing that they're about to die. And, you know, that was that that that's something that you can you can make animals have a much better life and still, you know, treat them as food, but start realizing that they have individual needs and they need, you know, a larger cage. They need to be able to move around. All of these kinds of things are ways that you can actually improve the systems we have existing without, you know, trying to bring everything down.

Eric 31:19

Yeah. Without trying to bring everything down, that that would be the key.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:23

That would be the gate now.

Eric 31:24

All right. Well, that's fascinating. Josh, thank you so much for that. I'll thank you. All right, folks, as I say, every time. Until next time.

.jpg)

_First_edition.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg/1200px-Blue_jay_in_PP_(30960).jpg)

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa